Crowdsourcing the Hall of Fame

15 January 2014

It’s a happy day for some of us at the GovLab when two of our favorite things — baseball and governance — intersect. This past November, the sports website Deadspin announced that it was seeking to acquire the 2014 Hall of Fame ballots of one or more of the voting members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA). Beyond setting out to mock what they claim is “an increasingly ridiculous election process”, Deadspin also sought in small part to democratize the Baseball Hall of Fame voting process by turning over the ballot to its readership. Ah, crowdsourcing and baseball — this is one way to pass the dreary winter months between the World Series and spring training, and test some ideas about the wisdom of the crowd and institutional resistance to change.

A very simple paper ballot containing an alphabetical list of these names is then mailed to BBWAA voters in late November. Electors can select up to ten names, and the ballot reminds them that “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.” Ballots are due back by December 31; any candidate receiving votes equalling or exceeding 75% of the ballots returned is then elected to the Hall of Fame. Blank ballots count toward the overall total, though unreturned ones do not.

As for the electors, these are active and honorary members of the BBWAA, people whose profession involves writing about baseball in newspapers; baseball broadcasters (such as Vin Scully) and most bloggers are excluded from voting. For the 2014 induction year, 571 ballots were returned — a 90 to 95% response rate (the Hall says “more than 600 voting members” received ballots) that is right in the ballpark for most years. While members are encouraged to keep their votes confidential until after the results are announced, the Association releases the ballot results of electors who choose to make their choices known (some writers also release their votes through their own publications).

The results released in early January found that three players of the 36 on the ballot — Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine and Frank Thomas — exceeded the 75% threshold and were elected in their first year of eligibility. (Craig Biggio, in his second try, fell two votes short and will have his name considered again next year). Out of all voters, there was only one trifecta matching the groups’ choices — Angel M. Prada’s selection of Maddux, Glavine and Thomas as his only choices mirrored the three players selected for induction by all writers.

So that’s how the experts decided who was Hall-worthy, using their traditional voting method. Our interest here is in comparing how the crowdsourcing approach that Deadspin facilitated compared in terms of outcome (results from a poll on the NPR website are also available). The Deadspin readership is typified by the highly enthusiastic and knowledgeable baseball fan (notice I didn’t use the term “rabid” or “fanatical”), possessed of a deep “inside baseball” knowledge of the game and strongly-held preferences and opinions. The more general audience of NPR listeners and website visitors exists as a sort of control group – though likely containing a number of people who own complete boxed sets of certain Ken Burns documentaries on DVD.

Neither the Deadspin nor NPR votes can be directly compared to the BBWAA process. In particular, Deadspin’s voting process was modified from the BWWAA process in a couple of significant respects beyond just the use of an online voting system. Anyone with access to the Deadspin website was able to vote for or against as many or as few of the 36 candidates on the ballot. To translate these votes into a selection on the official ballot that Deadspin obtained from the BBWAA writer, a candidate would have to secure a majority of votes in favor of their selection (e.g., if 1000 voters selected either yes or no for a player, he would have to have received 501 or more yes votes to be selected). If more than ten players exceeded 50%, the top ten vote winners would be selected on the official ballot.

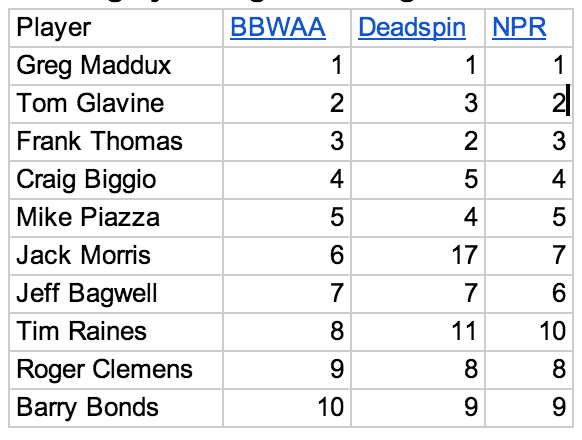

In each case, however, the voting processes yield a preference ranking that can be directly compared. The ranking of players based on the percentage of votes cast in their favor in each process is as follows (the full data table is available).

Ranking by Voting Percentage Obtained

What is remarkable is how comparable these lists are. Except for some minor re-ordering, the NPR list is very similar to the BBWAA list. And except for the low ranking of Jack Morris in the Deadspin list (the reason for which bring us deep into the esoteric world of Sabermetrics), and a preference for Edgar Martinez and Curt Schilling, there is also much overlap between this and the BBWAA list. That Maddux, Glavine and Thomas were the top three selected players in all three processes should cause the BBWAA leadership to at least consider the possibility of wisdom in the crowd. It should also cause the writers at Deadspin the re-evaluate whether the members of the BBWAA are universally-idiotic. For those who look at all this and are inclined to say “but it’s just a game”, one thing stands out in the back-and-forth invective: these baseball-types sure do take this pastime seriously.

Regardless of the apparent wisdom in the crowd, the BBWAA took a very dim view of the idea of crowdsourcing the vote: when the identity of the writer who turned over his ballot to the crowd was revealed as Dan Le Batard, columnist for The Miami Herald, he was suspended as a member of the BBWAA and stripped of his right to vote in future Hall of Fame processes. Le Batard and Deadspin were roundly criticized by baseball writers for turning over his vote to the judgement of an anonymous crowd, and for seeking to destabilize the nearly century-old BBWAA process. While the official reason that he is being punished is because he transferred his “ballot to an entity that has not earned voting status” (something that other writers have openly done in the past), the essence of the controversy seems to be that the wisdom of the experts — as embodied in the voting members of the BBWAA — is preferred by baseball insiders to the “wisdom” of the crowd. (Perhaps not insignificantly, there is controversy because the primary motive of the exercise was to mock the voting process and the BBWAA itself; had the voting taken place and the results transferred anonymously, the response — if any — of the Association would likely have been quite different).

In many respects, this is a story of somewhat defensive insiders protecting traditions, and disgruntled outsiders seeking to disrupt the power structure they are excluded from. That bloggers and broadcasters are not part of the BBWAA tradition, and non-voters are questioning the legitimacy of the Hall of Fame selection process because of their exclusion, is a function of a rapidly changing media landscape. Separating the personalities from this as much as is possible, and acknowledging that the first goal of every institution ultimately devolves to ensuring its own status and power (though, to be fair, the BBWAA is considering changes to the voting rules), what can the BBWAA learn from this?

The results of the Deadspin crowdsourced vote, as compared to the BBWAA process, reveal that there is indeed a comparable wisdom to be found in the crowd. And while it involves a leap of faith, a procedurally secure process with a large number of voters will likely yield a result comparable to what an expert panel would conclude, and lend the process greater perceived legitimacy. There are indeed special circumstances at play in this case, not least of which includes the impressive “inside baseball” knowledge of baseball fans who appear to spent significant amounts of time reading and commenting in baseball blogs. Not every governance setting is so fortunate to have an electorate that both has a detailed knowledge of the substance of the topic under debate, and a focused belief of the importance of the outcome. Investigating where these special circumstances can be found in other settings is part of a larger research agenda at the GovLab, seeking out the conditions under which crowds can be counted on to make wise decisions.

That a crowdsourcing approach to determining who should enter the Hall could work won’t surprised some baseball fans, though. While we may have significant disagreements about our favorites, we generally agree that there is a lot of collective intelligence to be found in the bleachers.